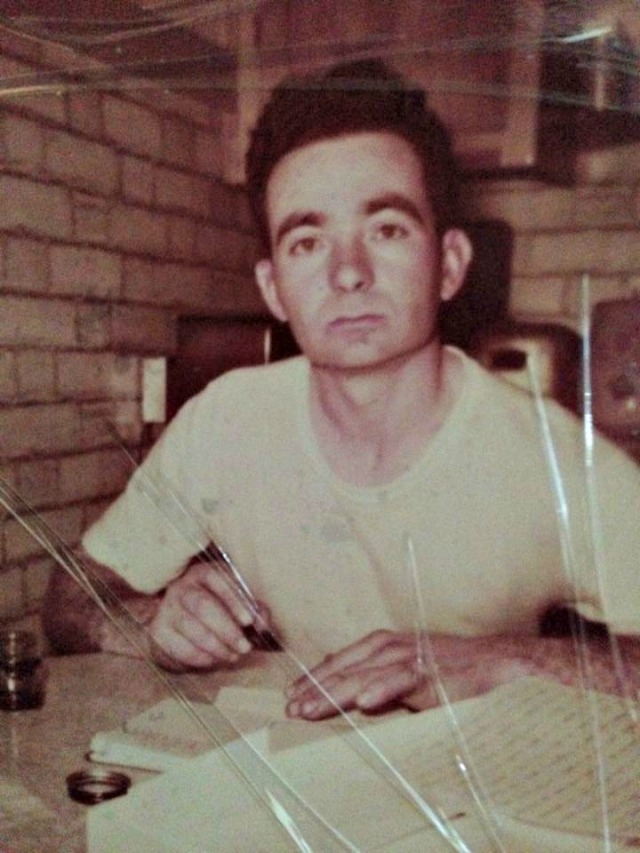

This photo of my father was taken in Blue Island, Illinois roughly four years before I was born. Ermelindo D’Aversa was born in 1922 in Montella, a small town in the mountains of southern Italy. My mother, Teresa Iuliano, had been born there, too, in the same year. My mother came to the United States as a young teenager. She married the man who would become my father in 1948, during a lengthy visit with family in Italy. Teresa then went home to America, as scheduled, and Ermelindo followed later, after he obtained the necessary funding and approvals.

In 1949, this man flew to the United States, arriving as he described it, “$200 in debt and with nothing but the clothes on my back and the suitcase in my hand.” While growing up in Italy, he had completed the then-required five years of formal education, but spoke little to no English, other than what he might have picked up while assigned to a company of British soldiers after the end of World War II. His role, as they moved from village to village across Italy, was to inform the frightened citizens that the war was over and that these English soldiers were not going to kill them. Go ahead, try to imagine what that job must have been like.

Prior to the war, my dad had been a policeman, a member of the Carabinieri. When the war broke out, he immediately became what can best be described in our understanding as military police. He spent most of his time patrolling an island where political prisoners, at least those who were not killed outright, were sent. The residents of that island could pretty much come and go as they pleased, but they were confined to that island.

My dad did not talk about the war much, not until the final years of his life, which is when I learned most of what I am sharing here. He had nothing good to say about war and he absolutely despised any movies or television shows that glamorized war, but it wasn’t until near the very end of his life that he spoke to me about why. In terms of all the carnage and destruction, he summed it up saying, “You can’t come back from that and be the same young, innocent man you were before you went.” He was in his late eighties and dying when we finally had these conversations. Until then, he had just kept it all inside.

My father was not a highly educated man, but he made the most of what he had been given. He had a very keen sense of right and wrong, which he considered fundamental and irrefutable. Indeed, he would laugh out loud at arguments that actions that were wrong yesterday could somehow be okay now. “Two and two cannot become five,” he would offer, shaking his head in amusement. He also possessed a very strong sense of respect for age and experience, even before he became the oldest… and even if the elder person were wrong. Once during a heated discussion about his own father, who had been very strict in raising his seven children, my father assured me, “Back then, if our father said two and two are six, we said yes!” Then I was the one shaking my head.

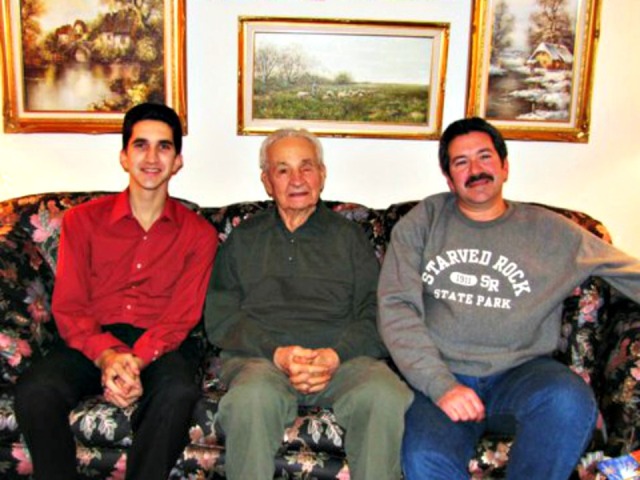

In 1992 I became a father myself. Not understanding what I was getting myself into, I did it again in 1993. Even then I think I understood that I could never be the same father to my children that my father had been to me, no more than my dad could have copied his father. It just doesn’t work that way. Still, I wish I could have done better. And when I look back at how much my father accomplished with so little, I feel downright ashamed.

- Despite never having achieved a higher role than that of a non-union laborer, he put his three children through parochial grade schools, me through a Catholic high school, and darned near paid for all three of us to complete at least four years of college.

- I’m guessing that he never made more than $30,000 a year, if that much, yet at his passing, following twenty years of retirement, one-third (my share) of his savings was still far more than my wife’s and my savings at the time, despite our dual incomes (and we couldn’t maintain the level of savings we had taken on).

- Despite having been far less educated and far less articulate than me, he demanded more from his wife and children than I ever could—and he got it, period.

Yeah, so in view of all that and more, I tend to get a little down on myself as a dad. I’ve always been softer on my kids, more lenient, more willing to let them go see what they can accomplish rather than attach values to their desires. But I’ve also always been more of a free spender, a pleasure seeker, more willing to have fun today than put away for tomorrow. And my children, who are now adults themselves, have both examples to consider.

In the end, we reap what we sow. While there can be no doubt that I am my father’s son, I have clearly taken things in a different direction than he would have. That’s on me and while I may have some regrets, I make no apologies for the choices I have made. Those choices were mine to make.

And I’ll go you one better. I am grateful to my father for having made those choices possible for me, good or bad. I am proud of my parents, proud of my Italian heritage. And as a dad myself, I am proud of my children. Despite our own shortcomings, somehow my wife and I have given them a decent foundation upon which to build. The chapters they will write going forward hold many possibilities. Wait and see.

Good rreading

LikeLike