Yesterday my son and I buried our fig trees for the winter. Well, we buried one and removed another that had been struggling for two years now. Most people look at me funny when I talk about burying trees. Some people look at me funny when I talk about growing figs where I live, because they don’t believe one can grow figs in this latitude. I can state from experience that yes, you certainly can grow fig up here, but it isn’t necessarily easy.

When I was growing up in the Chicagoland suburb of Blue Island, many of the “old Italians” kept fig trees. My father had kept three or four going at any given time. My grandfather across the street had a couple. My uncle “below the hill” (Blue Island’s east side, which was predominantly Italian at the time) had some, as did some cousins and assorted paesani. As you might imagine, fresh figs were abundant among my extended family during the growing season.

Wait. Can you imagine? Do you know what a fresh fig looks like? Perhaps I’d better back up a little.

Figs are a tree/shrub fruit that grow throughout the tropics, Asia and the Mediterranean. They have been around for a while. Indeed, fig trees are mentioned numerous times in both testaments of the Bible. If you are familiar with the book of Genesis, you know that after having eaten from the tree of knowledge, Adam and Eve used fig leaves to cover their nudity. The gospels of mark and Matthew include accounts of Jesus cursing a barren fig tree, which proceeds to wither and die.

Figs are a tree/shrub fruit that grow throughout the tropics, Asia and the Mediterranean. They have been around for a while. Indeed, fig trees are mentioned numerous times in both testaments of the Bible. If you are familiar with the book of Genesis, you know that after having eaten from the tree of knowledge, Adam and Eve used fig leaves to cover their nudity. The gospels of mark and Matthew include accounts of Jesus cursing a barren fig tree, which proceeds to wither and die.

Figs themselves (i.e. the fruits) are considered aphrodisiacs and their unique shape and characteristics are representative of both the male and female sex organs. Without getting too graphic here, the whole fruit is thought to resemble a man’s family jewels, while the cross section bears a resemblance to the female… um.. that is… oh, my. Well, anyway…

Figs themselves (i.e. the fruits) are considered aphrodisiacs and their unique shape and characteristics are representative of both the male and female sex organs. Without getting too graphic here, the whole fruit is thought to resemble a man’s family jewels, while the cross section bears a resemblance to the female… um.. that is… oh, my. Well, anyway…

Presumably because of their thin bark and high water content, fig trees were not designed to withstand our harsh Midwest winters. I have no idea who first had the idea to preserve fig trees by burying them during the winter months, but the practice clearly works. As I said earlier, the process isn’t easy. It isn’t even particularly fun. And the larger the trees grow, the more difficult the process becomes, until finally it becomes impossible, at which point the tree remains standing during the winter months – and dies.

So how does one bury a fig tree? I’m glad you asked. In mid-to-late autumn, after all the leaves have dropped and there is little to no chance of another warm-up before winter arrives, you prepare the tree for burial by pruning and bundling the branches into a narrow, manageable package. Then you dig a trench from the base of the tree outward. The length of this trench must be equal to or slightly greater than the height of your tree. I should also mention that each year (this is an annual process), the trench will be dug in the same direction.

So how does one bury a fig tree? I’m glad you asked. In mid-to-late autumn, after all the leaves have dropped and there is little to no chance of another warm-up before winter arrives, you prepare the tree for burial by pruning and bundling the branches into a narrow, manageable package. Then you dig a trench from the base of the tree outward. The length of this trench must be equal to or slightly greater than the height of your tree. I should also mention that each year (this is an annual process), the trench will be dug in the same direction.

The idea is to bend/pivot the fig tree at the roots level, beneath the soil surface. Mind you, the tree will not want to lie down. It will help to loosen the soil around the base of the tree and gently rock the tree back and forth until it is willing to lie down for a winter nap. I should also point out that in the spring, this same tree that resisted laying down will also not want to stand back up. Such is the stubborn nature of a fig tree.

Once the tree has been convinced to lie down in the trench you’ve dug, you must cover the trench with boards, corrugated metal, etc., forming a sort of protective tomb for the tree. Then you pile dirt on top of the covering, closing off air flow and providing an insulating layer from the harsh elements of winter. In order to let moisture escape, my father would fashion a breather vent from an old section of downspout and some window screen material. Worked like a charm, so I began using them, too.

Once the tree has been convinced to lie down in the trench you’ve dug, you must cover the trench with boards, corrugated metal, etc., forming a sort of protective tomb for the tree. Then you pile dirt on top of the covering, closing off air flow and providing an insulating layer from the harsh elements of winter. In order to let moisture escape, my father would fashion a breather vent from an old section of downspout and some window screen material. Worked like a charm, so I began using them, too.

The first time I tried this process, I failed. My father had given me a shoot from one of his mature trees and advised me to take it home, stick it in the ground, keep it watered and see what happens. The shoot took – under the right circumstances, fig trees are very prolific (must be all that sexuality with which they are associated) – but when it came time for winter burial, either the tree had not yet been established enough to withstand the process or my methodology was somehow off. In any case, the little tree died. I felt terrible.

The following summer, my dad handed me another shoot, its base wrapped in a ball of newspaper containing a quantity of the tree’s native soil. “Try again.”

“But Pop…”

“Try. See what happens.”

I’ll tell you what happened. I failed again. The shoot threw roots and sprouted a few new leaves, but did not survive winter burial. By this time I had become quite willing to give up and leave the fig tree cultivation to people who knew what they were doing.

My dad had other ideas. The following summer, he once again handed me another shoot, nicely wrapped in a ball of dirt surrounded by newspaper. “Try again.”

I could not refuse. I took the shoot home, stuck it in a patch of cultivated soil, kept it watered, watched it take root, etc. Then, when the last leaves had fallen, I dug a tiny trench, for a tiny tree, laid the little guy down, as I had been instructed, covered the trench with a length of plywood, covered the plywood with an ample amount of dirt, then crossed my fingers and waited until spring.

At the appropriate time, I unearthed the entombed little tree, my third attempt at a craft that my dad had made to look so easy. Weeks went by… nothing. Still I waited. More weeks went by. Then one morning I walked past my kitchen window and glanced out toward this stick standing up in the middle of my garden… and saw something green. Green!

I ran outside to confirm it. Yes, that speck of green was indeed the start of new leaf growth! Then I ran back inside and called my father just as quickly as my shaking fingers could dial.

“Pop!”

“Hey.”

“Pop! Guess what! The little sonofabitch is alive!”

“Eh?”

“The fig tree! My fig tree!! It’s alive! I did it!”

“See? I told you…”

Thus began my love affair with the common fig tree. A month or so later, my father proved his faith in my ability by presenting me with yet another shoot from one of his trees.

“Here,” he commanded and he thrust the carefully wrapped bundle into my reluctant hands. “Take it home, stick it in the ground, keep it watered…”

By then I knew the drill. But even more importantly, by then I knew it could be done! A year later I had two thriving trees. At first they yielded only a handful of undersized (but delicious) fruit, but a few years later, I was collecting enough full-sized figs to warrant giving some away. I was happy. My father was proud. Life was good.

By then I knew the drill. But even more importantly, by then I knew it could be done! A year later I had two thriving trees. At first they yielded only a handful of undersized (but delicious) fruit, but a few years later, I was collecting enough full-sized figs to warrant giving some away. I was happy. My father was proud. Life was good.

In the few years leading up to my father’s death in 2011, I began taking over the burial and resurrection of his fig trees, which were much more mature than my own. During those years, two wonderful things happened. First, my dad was able to watch and counsel me on the finer points of this craft. But at the same time, my son was able to begin learning, first by watching us and then by actively assisting my father and me.

Today, at the age of 22, my son knows as much about this process as I did when I was 20 years older than him. More often than not, we work the trees together. I believe my father would have been proud. I know I am.

My memories of Thanksgiving are not exactly the stuff of Norman Rockwell illustrations. Oh, there have been plenty of fond memories, just not your typical textbook Americana vignettes. For one thing, I didn’t grow up in a traditional American household. My mother and father were Italian immigrants, as was the overwhelming majority of my cousins. I was born here, but my first words were probably spoken with an Italian accent.

My memories of Thanksgiving are not exactly the stuff of Norman Rockwell illustrations. Oh, there have been plenty of fond memories, just not your typical textbook Americana vignettes. For one thing, I didn’t grow up in a traditional American household. My mother and father were Italian immigrants, as was the overwhelming majority of my cousins. I was born here, but my first words were probably spoken with an Italian accent. The traditional American Thanksgiving dinner consists of roast turkey with cranberry sauce and dressing, mashed potatoes, green beans and other assorted goodies. My Thanksgiving dinners came with most of that, plus a steaming bowl of homemade pasta smothered in homemade tomato sauce and a huge platter of meat that had spent hours simmering in that sauce – things like homemade meatballs, braciole and salsiccia (aka fresh Italian sausage). There was always homemade wine and homemade bread on our dinner table. The insalata – a tossed salad dressed with vinegar and oil, plus a small plate of olives on the side, in case anybody wanted some – came after the main course and before the dessert, which may have included pumpkin pie, raisin pie (my father’s favorite), biscotti, and who knows what else.

The traditional American Thanksgiving dinner consists of roast turkey with cranberry sauce and dressing, mashed potatoes, green beans and other assorted goodies. My Thanksgiving dinners came with most of that, plus a steaming bowl of homemade pasta smothered in homemade tomato sauce and a huge platter of meat that had spent hours simmering in that sauce – things like homemade meatballs, braciole and salsiccia (aka fresh Italian sausage). There was always homemade wine and homemade bread on our dinner table. The insalata – a tossed salad dressed with vinegar and oil, plus a small plate of olives on the side, in case anybody wanted some – came after the main course and before the dessert, which may have included pumpkin pie, raisin pie (my father’s favorite), biscotti, and who knows what else. When I was a child, back in the 1960’s, there were still a good number of live poultry shops in the Chicago area. And since my grandfather, who briefly shared ownership of a small restaurant, refused to eat any bird we hadn’t killed ourselves, the centerpiece of our Thanksgiving dinner was usually still walking during the wee hours of Thanksgiving morning. I still recall a particularly traumatic experience I had one Wednesday afternoon prior to Thanksgiving, when I ran down to the basement of our Blue Island home, probably looking for my father, and came face-to-face with a tom turkey that was every bit as tall as I was. Maybe taller. We both stood there for a moment, staring at each other in the dim light of what was remaining daylight filtered through a small basement window above our heads.

When I was a child, back in the 1960’s, there were still a good number of live poultry shops in the Chicago area. And since my grandfather, who briefly shared ownership of a small restaurant, refused to eat any bird we hadn’t killed ourselves, the centerpiece of our Thanksgiving dinner was usually still walking during the wee hours of Thanksgiving morning. I still recall a particularly traumatic experience I had one Wednesday afternoon prior to Thanksgiving, when I ran down to the basement of our Blue Island home, probably looking for my father, and came face-to-face with a tom turkey that was every bit as tall as I was. Maybe taller. We both stood there for a moment, staring at each other in the dim light of what was remaining daylight filtered through a small basement window above our heads.

Was I nervous? Not at all. I was scared. But we did it! And together with all the other motorcyclists, we raised $325,092 for pediatric brain tumor research that day. Thus began a new tradition for Teresa and me. My daughter and I have been raising money for pediatric brain tumor research by actively participating in the Chicagoland Ride for Kids every year since 2003.

Was I nervous? Not at all. I was scared. But we did it! And together with all the other motorcyclists, we raised $325,092 for pediatric brain tumor research that day. Thus began a new tradition for Teresa and me. My daughter and I have been raising money for pediatric brain tumor research by actively participating in the Chicagoland Ride for Kids every year since 2003. And so it continues, year after year. Me, I wouldn’t miss this for the world. And now you know why. Thanks for listening.

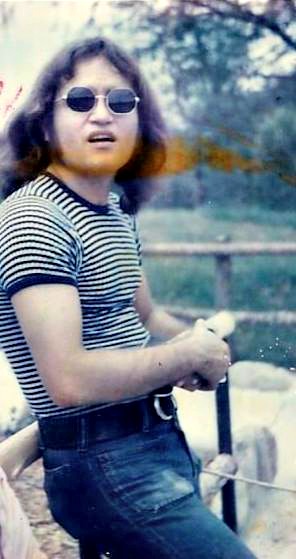

And so it continues, year after year. Me, I wouldn’t miss this for the world. And now you know why. Thanks for listening. This guy I used to know from Blue Island passed away suddenly and unexpectedly on October 30. His name was Joe Mangione and he was a close friend of my older cousins in town, whom I idolized when I was growing up. He was in the Army during the Vietnam era, as were a couple of my cousins. He also rode motorcycles, as did my cousins – they were the ones who got me hooked before I even started grade school. Our knowledge of each other would have been limited to that – seeing each other at my uncle’s house in the 1960’s and early ’70’s, and perhaps at a few of my cousins’ parties thereafter – except that Joe and I had the pleasure of working together for a short period of time.

This guy I used to know from Blue Island passed away suddenly and unexpectedly on October 30. His name was Joe Mangione and he was a close friend of my older cousins in town, whom I idolized when I was growing up. He was in the Army during the Vietnam era, as were a couple of my cousins. He also rode motorcycles, as did my cousins – they were the ones who got me hooked before I even started grade school. Our knowledge of each other would have been limited to that – seeing each other at my uncle’s house in the 1960’s and early ’70’s, and perhaps at a few of my cousins’ parties thereafter – except that Joe and I had the pleasure of working together for a short period of time.

I had none of the above. But between Joe, Frank, my other cousins and a handful of other east side regulars who frequented the station, I had my role models – at least for one magical summer.

I had none of the above. But between Joe, Frank, my other cousins and a handful of other east side regulars who frequented the station, I had my role models – at least for one magical summer. Yes, that was pretty good, but let me tell you my favorite Joe story. If this doesn’t illustrate how cool Joe could remain under pressure, I don’t know what would. We had been bleeding the brakes – a necessary step to remove any air bubbles that may otherwise remain in the lines following a brake job – on an early ’70’s Chevy Chevelle. It’s a simple enough operation. I went up with the car on the lift, while Joe tended to the brake lines. He would tell me to pump the brakes or depress and hold the brake pedal, as he opened and closed each line accordingly. Once the job was done, the car would be lowered and started, at which point the brake pedal would need to be depressed and pumped up one more time, as the power steering pump restored brake pressure. Simple, right?

Yes, that was pretty good, but let me tell you my favorite Joe story. If this doesn’t illustrate how cool Joe could remain under pressure, I don’t know what would. We had been bleeding the brakes – a necessary step to remove any air bubbles that may otherwise remain in the lines following a brake job – on an early ’70’s Chevy Chevelle. It’s a simple enough operation. I went up with the car on the lift, while Joe tended to the brake lines. He would tell me to pump the brakes or depress and hold the brake pedal, as he opened and closed each line accordingly. Once the job was done, the car would be lowered and started, at which point the brake pedal would need to be depressed and pumped up one more time, as the power steering pump restored brake pressure. Simple, right?